What is a Trade War?

A ‘trade war’ begins when a country seeks to protect their domestic economy from foreign competition. This is achieved in several ways, with the most popular being via taxes on foreign imports or by subsidising local industries. The primary reason that countries engage in protection is to promote the economic strength of the home country, including employment, often at points when the global economy is weak, or when there is rising competition from foreign participants. Through stronger local industry a country becomes less reliant on imports from foreign nations, providing a stronger base from which to direct its own growth policies.

One can expect that large and dominant countries are the initiators in these protection-based policies as they have the necessary scale to make a meaningful impact with their actions. As these protection-based policies are proposed and set, global counterparts tend to react with a similar approach, leading to a ‘trade-war’, where both sides aim to weaken the competitive ability of the other.

Why do we have a potential trade war in 2018?

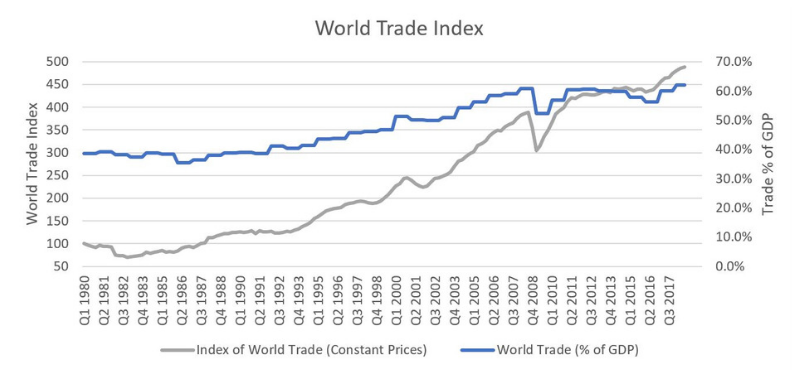

Over the past few decades there has been rapid growth in world trade, where Chart 1 below shows that global trade is almost five times higher in real terms today than it was in 1980. This increase in trade has seen jobs moving to cheaper labour markets, causing the erosion of industries in certain regions. Manufacturing jobs have gradually moved to the developing world (such as China) and led to job losses in the developed nations. The result is higher unemployment rates in developed market regions where manufacturing historically dominated the local economy. The protection of the local industries is therefore aimed to reduce the reliance on foreign countries and increase local employment.

Looking at history to see the patterns of past trade wars, we can assess two previous trade wars, both involving the US. The first is one which occurred in the lead up to the great depression when the US signed the Smoot-Hawley Act in 1930, with the intention to protect local businesses and farmers from a global slowdown. During the great depression world trade declined by 25%, about half of which has been attributed to trade barriers instituted by the act. The second is the 1980’s era trade war between a dominant US and a resurgent Japanese economy where the US imposed tariffs on Japanese electronics as well as limiting imports of cars and other steel-based products. This was done to protect the US from rising Japanese power. The outcome of this was the Plaza accord where Japan effectively gave in to US demands. Both instances mentioned above share some common elements: They both led to a decline in global trade and GDP[1] and in both cases the US emerged as the winner.

The current trade war has echoes of the 1980’s trade war with Japan as the US seeks to protect their dominant position in the world economy from developed peers as well as an increasingly powerful bloc of developing nations, led by China. The US believes that they have been exploited by their trading partners. They use the fact that they import more than they export to each of their major trading partners as evidence of this exploitation of free trade. Donald Trump ran for president on the back of a campaign to ‘Make America Great Again’. This campaign was centred on bringing manufacturing jobs back to the US from the developing nations, such as China and Mexico, and on supporting industries that had been decimated by the rise of global trade. The use of protectionism by the US is therefore a natural route for the president to follow to appease his support base.

What does this mean for investment markets?

In recent decades the global economy has become deeply interlinked, chart 1 shows that global trade has increased from 38% of global GDP in 1980 to almost 60% today. The larger size of global trade and deeper economic links between nations means that a trade war could have much deeper consequences than seen in previous instances.

The potential risks from this trade war are twofold. Firstly – global trade slows and this in turn slows global economic growth. This risk has been escalating with the IMF[2] releasing a report in mid-July 2018 that the current proposed tariffs (taxes) could wipe out 0.5% ($430bn) of global economic growth by 2020. To put this in context the current total size of South Africa’s economy is $426bn. This number has the potential to increase further as both sides escalate their trade-war policies. The second risk is that the taxes imposed on imports to the US push inflation up higher than expected. This, simplistically, would result in the US having to raise their interest rates at a faster pace than currently projected to compensate for the increased inflation. This course of action has the potential to cause a material decline in global asset values.

Either of the risks mentioned above would be negative for both developed and emerging markets. Developed nations have been beneficiaries of the rise in global trade with it opening new markets to sell their goods. Up to 30% of the revenue earned by companies in the S&P 500[3] comes from countries other than the US[4]. A decrease in trade would therefore negatively affect these companies’ revenues. Developing nations such as China and India have also been beneficiaries of the rise in global trade with many manufacturing jobs moving to these nations. Increased protectionism and a slow-down in trade would result in job losses and economic pressures in these nations’ export industries. In addition, the currencies and bonds of these emerging market economies could decline in value as the perceived risk of investing in these countries increases. South Africa would not be immune to these pressures as we too have been a beneficiary of the rise in global trade, with any slow-down in global trade and economic growth creating negative consequences for the country.

So what should investors expect from their portfolios?

Our view is that global trade is too entrenched and nations too interlinked to allow a prolonged trade war to occur. The level of price competition present in the global economy will force countries to come to a compromise on trade. The current trade war is therefore more short-term politicking than anything else. While certain counters may be impacted in the short term, we do not see a need to change the outlook on global trade longer term.

Specific shares may be exposed more than others – so we also caution against seeing any meaningful downside being applied in general across the market. Examples of this are car manufacturers such as Daimler (Mercedes-Benz) and Toyota whose profit expectations saw material negative moves as the trade wars intensified. A further example is Harley Davidson, a US based company which has indicated that the input costs per unit that they produce have increased by $2200 due to the tariffs imposed by the US on steel and aluminium.

However, we need to be careful not to be caught up in the constant ‘noise’ and headlines surrounding the potential for trade-wars. One could easily lay the blame for every recent downturn in world markets at the feet of the trade war. An example is the sell-off in emerging market bonds and equities in 2018. This has been roundly attributed to the trade tensions created by some news agencies when this sell-off has as much to do with a stronger US Dollar and rising US interest rates as it does with the trade war.

Given our views above we suggest that investors avoid the temptation to alter their long-term strategies. Stay the course through the higher volatility to come and ensure that portfolios are adequately diversified. The negativity surrounding the trade war has the potential to create investment opportunities for astute managers, and as investors we need to focus on the areas we have control over, and ensure that the areas where we don’t – such as trade wars – are appropriately considered within a broader portfolio.

Article by: The Fundhouse Team

1. GDP is a measure of the size of a region’s economy.

2. International Monetary Fund.

3. The S&P 500 is the most commonly quoted US equity market index.

4. Data source: FactSet Geographic Revenue Exposure (GeoRevTM) dataset.